In an astonishing feat of self-experimentation and scientific ambition, an American man has endured more than 200 snake bites and injected himself with venom over 700 times—an act of bravery, obsession, and unrelenting commitment that has now contributed to what researchers are calling an “unparalleled” breakthrough in snake antivenom therapy.

For nearly two decades, Tim Friede, a former truck mechanic with a deep fascination for venomous reptiles, voluntarily exposed himself to the world’s deadliest snake venoms. His goal? To build up his own immunity and ultimately help create a universal antivenom—a global game-changer that could save thousands of lives annually.

Today, Friede’s years of pain, close calls with death, and scientific curiosity have culminated in a remarkable scientific discovery. Researchers studying his blood have found antibodies with unprecedented breadth—ones capable of neutralizing venom from a wide range of elapid snakes, including cobras, mambas, kraits, and taipans. The implications of this are massive: a universal antivenom, long considered a near-impossible dream, may now be within reach.

The Making of a Living Experiment

The idea that someone would voluntarily subject themselves to lethal doses of snake venom sounds like science fiction—or madness. Yet for Tim Friede, it became a calling. Initially, his motive was personal: as a snake handler and enthusiast, he wanted to build resistance to venom in case of an accidental bite.

What began as an act of self-protection quickly spiraled into an intense mission that took over his life.

“I didn’t want to die. I didn’t want to lose a finger. I didn’t want to miss work,” Friede told the BBC in a recent interview. But after surviving two nearly fatal cobra bites that left him in a coma, something changed. “It just became a lifestyle and I just kept pushing and pushing and pushing as hard as I could push—for the people who are 8,000 miles away from me who die from snakebite.”

This sense of purpose transformed Friede’s self-experimentation into something far greater. He was no longer just chasing immunity for himself—he was chasing a breakthrough for the world.

Snakebite: A Global Health Crisis

Snakebites are one of the most overlooked yet deadly public health crises globally. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), snakebites claim the lives of as many as 140,000 people annually, with another 400,000 left with permanent disabilities such as amputations or disfigurement.

The burden of snakebite envenoming falls heavily on rural populations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where access to medical facilities and effective antivenom is often limited. The current standard treatment relies on antivenom made from the blood of animals—usually horses—who are immunized with specific snake venoms. These antivenoms, however, are highly species-specific. A serum effective against Indian cobras may be ineffective against Sri Lankan cobras. A mamba antivenom won’t help against a viper bite.

This specificity presents a dangerous problem, especially in areas with multiple venomous species and poor healthcare infrastructure. If victims are given the wrong antivenom—or if none is available at all—the consequences can be fatal.

That’s where Friede’s unusual blood comes in.

The Birth of a Breakthrough

The search for a better, more universal antivenom led researchers to explore the concept of broadly neutralizing antibodies—a type of immune response capable of targeting common structures across multiple toxins, rather than the unique markers of a single species.

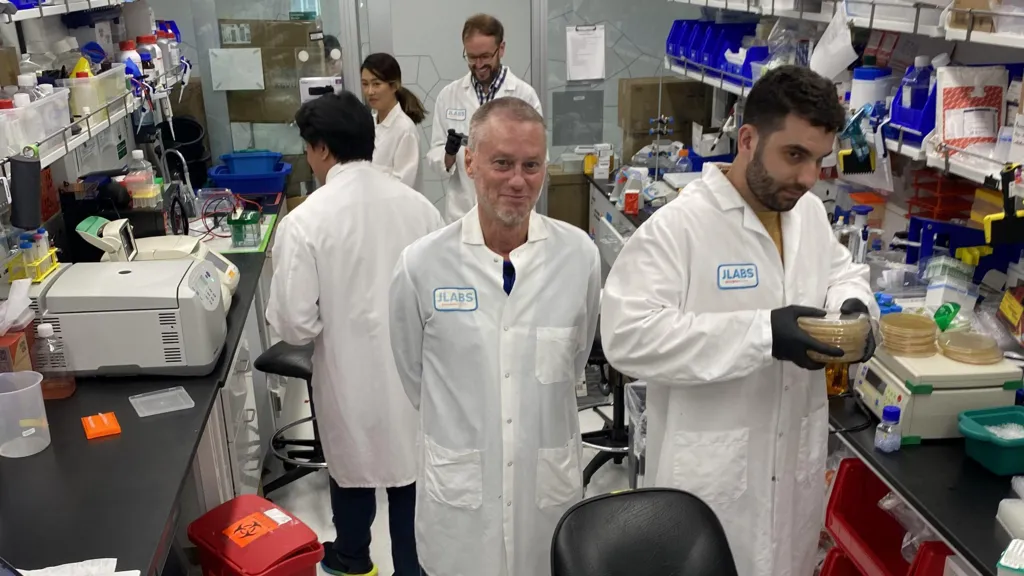

Dr. Jacob Glanville, the CEO of Centivax, a biotech company specializing in next-generation antibody therapies, was among those on the hunt. When he came across Friede’s decades-long work, he immediately saw the potential.

“If anybody in the world has developed these broadly neutralizing antibodies, it’s going to be him,” Glanville recalled thinking. “So I reached out. The first call, I was like, ‘this might be awkward, but I’d love to get my hands on some of your blood.’”

Friede, eager to further his mission, agreed. The study was granted ethical approval because it involved blood sampling, not additional venom exposure.

In the lab, researchers began analyzing Friede’s immune response against 19 different elapid snakes, each identified by the WHO as among the most dangerous on Earth. These include iconic killers like the black mamba, the coastal taipan, and various species of cobra and krait.

The goal was to identify whether Friede’s immune system had produced antibodies capable of neutralizing multiple neurotoxins—substances that paralyze and kill by shutting down the nervous system, particularly the muscles required for breathing.

What they found exceeded all expectations.

Inside the Antivenom Cocktail

From Friede’s blood, scientists identified two broadly neutralizing antibodies. These antibodies could counteract two major classes of neurotoxins. To round out the protection, researchers added a third, lab-designed drug targeting another venom component, forming a potent antivenom cocktail.

In animal testing, the cocktail proved to be a major breakthrough. Mice injected with normally fatal doses of venom from 13 out of the 19 species survived. The remaining six species showed partial protection—a result still far better than anything existing therapies offer.

“This is unparalleled breadth of protection,” Dr. Glanville said. “It likely covers a whole bunch of elapids for which there is no current antivenom.”

Prof. Peter Kwong, an immunologist from Columbia University and one of the leading researchers on the project, echoed the sentiment. “Tim’s antibodies are really quite extraordinary—he taught his immune system to get this very, very broad recognition.”

One Man, Global Impact

While researchers continue refining the cocktail—potentially adding a fourth antibody to improve coverage—the impact of Friede’s contributions cannot be overstated. What he endured physically and psychologically over nearly 20 years has given the scientific community a real-world roadmap to developing a universal elapid antivenom.

In total, Friede has injected himself with venom from more than 30 different species. He’s survived multiple near-death experiences, one of which left him with permanent damage to his nervous system. His hands and arms bear the scars of his commitment.

But for Friede, the pain has always been worth it.

“I’m doing something good for humanity, and that was very important to me. I’m proud of it. It’s pretty cool,” he said.

The Road Ahead: Vipers and Beyond

While the current research focuses on elapids, they are only one part of the equation. The other major group of venomous snakes—vipers—rely on haemotoxins, which destroy blood cells and tissue. Other venoms contain cytotoxins that directly kill cells, or myotoxins that damage muscles.

“There are about a dozen broad classes of toxins in snake venom,” said Prof. Kwong. “But I think in the next 10 or 15 years we’ll have something effective against each one of those toxin classes.”

This means that even broader, possibly universal antivenoms could become a reality—treatments that could be administered immediately without needing to identify the snake, a critical advantage in remote areas.

Prof. Nick Casewell, head of the Centre for Snakebite Research at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, called the breadth of protection “certainly novel” and praised the project as “a strong piece of evidence” that a universal antivenom is feasible.

Still, he cautioned that much work remains before such treatments are ready for widespread human use. The antivenom cocktail must undergo rigorous clinical testing, dosage refinement, and global regulatory approval.

A Legacy Written in Blood

The story of Tim Friede is not just one of science—it is also a story of sacrifice, obsession, and the human drive to solve problems that others ignore. While his methods were extreme and controversial, the impact is undeniable.

His blood, transformed into a scientific archive of resistance, could change the future for millions living under the shadow of deadly snakes.

And perhaps the most remarkable part of it all is this: Friede never did it for fame or fortune. He did it for the unseen victims thousands of miles away—those who never had a choice when snake venom came for them.

In his own words: “They die because they were born in the wrong place. If I can help change that, then every bite was worth it.”